Why Are Cellular Network Cells Hexagonal?

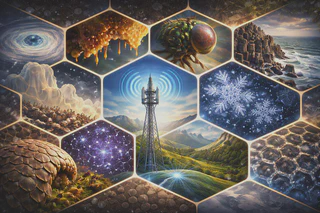

Look at Saturn’s north pole. There’s a storm there a perfect hexagon, wider than Earth, winds spinning at 320 kph, and it’s been there for over atleast 40 years (discovered in 1981).

Now zoom into a honeycomb. Bees build hexagons not because they’re following a blueprint, but because hexagons are the only shape that stores maximum honey with minimum wax. Physics forced their hand.

Carbon atoms arrange themselves into hexagons to make graphene: one atom thick yet stronger than steel. Snowflakes show six-fold symmetry.

Zoom into a dragonfly’s compound eye and you’ll see thousands of tiny facets packed in a near-hex grid, the most efficient way to tile a surface. Look at a basalt coastline like the Giant’s Causeway and the cooling rock fractures into columns that often settle into five- and six-sided shapes, with hexagons everywhere. Your eye’s light receptors? Hexagonal.

Even crystals get in on it: quartz belongs to a symmetry family that loves six-fold forms, and ice commonly grows with hexagonal symmetry, which is why snowflakes carry that signature. And in living armor, the way scales pack and overlap can drift toward hex-like neighbor patterns, because when many similar pieces must share space with minimal waste, six sides keeps winning.

And that’s exactly why cellular networks use it too.

This isn’t poetic coincidence. This is applied physics showing up at completely different scales and arriving at the same answer. The hexagon is nature’s compression algorithm—it’s what geometry looks like when you’re optimizing for efficiency.

It took mathematicians nearly 2,000 years to formally prove what bees already knew: the hexagon is the provably optimal shape for dividing a plane into equal areas with minimum perimeter. This proof (finally completed in 1999) is called the Honeycomb Conjecture.

1) The Coverage Problem: Efficient Tessellation

The primary challenge in cellular network design is area coverage with minimal overlap and gaps. We need to:

- Cover the entire service area uniformly

- Minimize wasted/overlapping coverage

- Design cells that are easy to implement and manage

- Ensure each cell can be served by a single base station

This is fundamentally a tessellation problem: which geometric shape best tiles the plane?

Candidate Geometric Shapes

Let’s examine the common options:

Circles:

- Advantage: Uniform coverage from a central base station

- Disadvantage: Circles don’t tile perfectly, there are always gaps or overlaps between adjacent circles

- Verdict: Not practical for a regular grid

Squares:

- Advantage: Easy to implement, simple coordinate system

- Disadvantage: Inefficient, corner cells have different propagation characteristics than edge/center cells

- Verdict: Works but suboptimal

Hexagons:

- Advantage: Perfect tessellation, all cells are identical, uniform distance from center to edges

- Disadvantage: Slightly more complex to implement

- Verdict: Optimal choice

2) Mathematical Advantages of Hexagons

Tessellation Efficiency

The hexagon is one of only three regular polygons that perfectly tile the plane (with triangles and squares being the others). But the hexagon has unique advantages:

Nearest Neighbor Distance:

- In a hexagonal grid with cell radius $r$, the distance to nearest neighboring cell center is constant: $d_{nn} = 2r$

- In a square grid with side length $s$, diagonal neighbors are at distance $\sqrt{2}s$ (farther than edge neighbors at distance $s$)

- This uniformity is critical for interference management and network planning

Coordination Number:

- A hexagon has 6 nearest neighbors (equidistant)

- A square has 4 edge neighbors and 4 diagonal neighbors at different distances

- This uniform neighbor structure simplifies interference analysis

Coverage Uniformity

The hexagon provides uniform coverage characteristics in all directions from the cell center:

- The maximum distance from cell center to any point in the cell (circumradius) is the same in all directions

- In a square, corner points are farther from the center than edge points

- This uniformity reduces coverage “dead zones” and simplifies resource allocation

3) Interference Management Perspective

In cellular networks, interference is the limiting factor on capacity. The hexagonal structure helps optimize interference patterns:

Co-channel Interference:

- Cells operating on the same frequency should be placed at sufficient distance to avoid strong interference

- Hexagonal geometry enables regular frequency reuse patterns (e.g., 3-cell reuse, 7-cell reuse)

- The regular structure means interference sources are uniformly distributed around any cell

Distance to Interferers:

- For a 7-cell reuse pattern in a hexagonal grid, co-channel cells are at a distance of $\sqrt{21} \cdot r$ from the center cell

- This clean mathematical relationship makes system design tractable

4) Practical Implementation

Despite the mathematical elegance, real deployments use several variations:

Theoretical Ideal:

- Perfect hexagonal grid with one base station per hexagon

- Antenna oriented optimally for 120° coverage sectors

Practical Reality:

- Terrain and obstacles distort ideal coverage

- Actual cell coverage is determined by propagation measurements, not geometric shapes

- Sectorization (120° sectors) effectively creates 3 cells per site

- Small cells, femtocells, and heterogeneous networks layer different cell sizes

5) Hexagonal Cells in 3GPP System Level Simulations

Despite the messy reality of terrain and irregular site placement, 3GPP-style system-level evaluations often use a regular hexagonal grid (frequently 19 sites with 3 sectors per site) as a reference geometry so results are repeatable and comparable across companies and simulators.

For example, 3GPP TR 38.901 (NR channel model) specifies scenario layouts such as “Hexagonal grid, 19 sites, 3 sectors per site”, together with scenario-dependent inter-site distances (ISD) (e.g., UMi street canyon: 200 m; UMa: 500 m).

- TR 38.901 PDF: https://www.etsi.org/deliver/etsi_tr/138900_138999/138901/16.01.00_60/tr_138901v160100p.pdf

A common companion technique is wrap-around, used to suppress border effects so interference statistics resemble an “infinite” network. 3GPP TR 25.700 explicitly lists “21-cell hexagonal (7 sites, 3 sectors/site) with wrap-around” and “57-cell hexagonal (19 sites, 3 sectors/site) with wrap-around” as system simulation layouts.

- TR 25.700 PDF: https://www.arib.or.jp/english/html/overview/doc/STD-T63V12_10/5_Appendix/Rel12/25/25700-c00.pdf

This same reference layout appears across earlier study items as well—for instance 3GPP TR 36.873 (3D channel model for LTE) uses “Hexagonal grid, 19 sites, 3 sectors per site” for UMi/UMa-type scenarios.

- TR 36.873 PDF: https://www.freecalypso.org/pub/GSM/3GPP/archive/36_series/36.873/TR36.873%20v1.0.0%203D%20channel%20model%20for%20LTE.pdf

6) Why Not Other Shapes?

Triangles:

- Tile perfectly but have poor coverage properties (very non-uniform distance from center)

Pentagons:

- Don’t tile the plane regularly

Circles:

- Can be made to work with careful overlap management, but mathematically inefficient

Irregular patterns:

- Possible with advanced optimization, but lose the planning simplicity

Conclusion

The hexagonal cell is not just a convenient abstraction, it’s the mathematically optimal solution for the cellular coverage problem. It provides:

- Perfect tessellation with no gaps or overlaps

- Geometric uniformity ensuring consistent coverage and interference characteristics

- Symmetry enabling regular frequency reuse patterns

- Simplicity in network planning and optimization

While modern networks increasingly use heterogeneous deployments with multiple cell sizes and irregular patterns, the hexagonal principle remains foundational to how we think about cellular network design.

The next time you see that iconic hexagonal grid pattern, you’ll know it’s not just a convention—it’s the elegant solution to a fundamental problem in wireless communications.

Comments